What Made Us Interested In Graphql

When I try to trace back why I think GraphQL is a good fit for us, I always end up somewhere in the years 2012, 2014 and 2016. Apologies upfront, this is going to be a long one.

2012

In 2012 I started working for XING in the API - team. Together we launched XINGs public REST API that same year. The infrastructure for that had already been in place for roughly two years (I think) and was also the data source for XINGs own native mobile applications. In fact many of the APIs that you would find later in the public REST API originated in the context of those applications and at least for a short time there was a 100% overlap between the public API and what the mobile apps were using.

One thing we already had at that time was a query parameter called fields on the users API and user_fields on every API that was referencing users. These query parameters expected a comma separated list of field names and if you would call the API that way, you’d only get back what you had requested. It even supported nesting so you could request business_address.city to only get the city portion of the business address. If you look at it now from a GraphQL perspective, you might think “wait a minute, that sounds almost like a mini selection set” and I think this isn’t too far off. It had the same benefits (tracking, e.g. who is using what and bandwidth optimization, e.g. only transfer what the client actually needs) but obviously ours was a very simple, poor mans version of the idea.

Unfortunately, driven by the overarching goal to make things as straightforward to use as possible, the team looked at this only as an optimization. If you didn’t specify the fields, you would get everything. I bet you can already guess what happened: While our mobile applications made good use of this, most of the other consumers of the public API didn’t, which kinda neglects at least the transparency benefit.

Talking about change, I think there’s a field of tension if you’re attempting to re-use a public API for your mobile applications (or the other way around) like we did. Good public APIs are like a promise of stability. They change very infrequently. You can rely on them and build solid, long living integrations on them. And judging from my experience, it takes significant time to design them that way.

On the other end of the spectrum are your own mobile applications where you (or at least the company) more often than not want to iterate fast, get features out as fast as you can and learn based on actual usage. These two things were always at odds at the time. Often the desired change some of our product teams wanted to make wasn’t easily possible without breaking existing consumers of the public API, or introducing some kind of versioning which we tried not to do at the time (since we just had come out with the v1 of the API).

Side joke: Guess what the version number of the public API is in 2018?

Usually we would end up with either additional API calls to get the necessary data or adding the necessary data to existing APIs. The former with the downside of complicating life for the frontend people (request coordination, timeouts and partial results where one API succeeded while the other didn’t) and the latter with delivering data to consumers that they didn’t need and would simply throw away.

This is usually the spot where somebody from the internet storms in and points out in good old Kevin Sorbo style that “this ain’t REST !!!”. Congrats, you’re correct. Like most people at the time we were labeling our API as

RESTeven though what we actually had (also like most people :)) was just a good old CRUD API implemented withHTTPandJSON. Let’s move on, shall we?

But we did have a lot of talks about the “real REST”, this elusive unicorn. My colleagues from that time can probably acknowledge that I in particular might have been pretty much a pain in the ass about that one, at least for some time. Like many people at the time I’ve read Fieldings thesis and the few available books for that topic. I was exited about it because it seemed to offer a way out of the coupling problems we experienced with our API consumers (if the client played by the rules).

Whenever I tried to convince my peers though, the excitement grinded to halt in record time. Discussions usually ended with blank stares, when we came to the point clients had to do in order to make the Hypermedia game work.

ME: So, what do you think about that?

MOBILE DEV: …. (silence) …. (more silence) …

API DEV COLLEAGUE: … “So, you kinda want him to turn our mobile app into a browser?”

MOBILE DEV: … “Listen, I just want to get some data …”

Remember part of the teams mission statement was to make the APIs as easy and self explaining as possible. Having an additional protocol in between wasn’t on the “hot things” list. At the time this frustrated me, but with some distance I have to admit, they probably had a point. Part of their non-enthusiasm for the idea boiled down to the fact that there wasn’t (and to my knowledge still isn’t) a widely adopted standard (at least if you exclude HTML) with good tooling and library support in multiple programming languages. Everything would need to be created from scratch by us.

Ultimately this experience made me realize that whatever solution might appear in the future that would improve the API game for mobile applications, it would be one with a very good developer experience and strong, multi platform tooling support.

2014

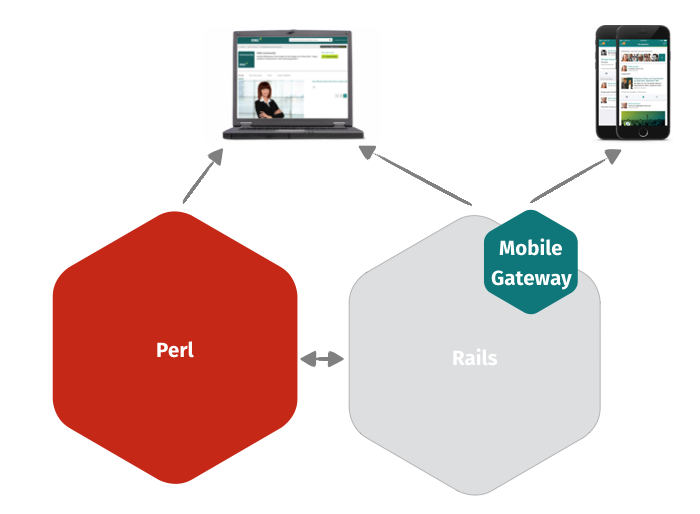

Between 2012 and 2014 something interesting happened somewhere else inside XING. When I started in the company in 2012, the majority of the developers was still working in one of two monolithic applications. One being written in Perl (the original OpenBC) and another one in Ruby on Rails (containing all recent developments). The API infrastructure was part of the big Ruby on Rails application. Overall it kinda looked like this (I’m obviously omitting some details here for simplicity):

All in all it was pretty web and desktop centric. APIs and mobile played a subordinate role at the time. A larger project was run by the Architecture team to break apart the Rails monolith and introduce HTTP+JSON APIs in between. The Perl monolith followed the same path roughly 2 years later. Luckily most extracted Perl code also got rewritten in a different language :-).

XING was already experiencing the first wave of organizational growth challenges and the platform architecture moved into the direction of something akin to a service oriented architecture. With that request coordination, timeouts and partial results also became something to deal with for the backend applications.

People are usually surprised when they see this picture because they wonder where the presentation tier is. Yes, for a long time at

Railsand were just exposing their content in different formats:HTMLandJSON. Later it became more and more practice to separate the two, but more on that in a second.

I had moved on from the API team and after a short stint working on our hybrid iPad application, I found some new interesting challenges in the Architecture team.

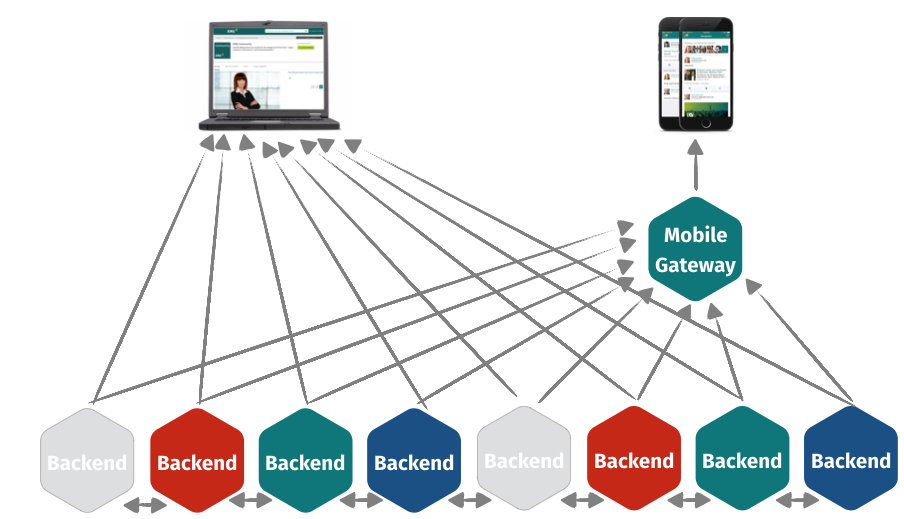

Another trend in 2014 emerged: Mobile first. And with that the development resources for the native mobile applications were heavily scaled up. What became obvious pretty fast was that the API team, as the primary data source for the mobile applications, became an organizational bottleneck, because more and more teams were waiting for new APIs to appear. It was a classic Littles Law effect. Demand went up, capacity stayed the same and waiting queues started to form. The organization didn’t take long to react and somewhere during 2014 we made the decision to distribute the responsibilities for building the mobile APIs to all backend applications. The infrastructure for the public API was still re-used for it, but limited to a simple proxy dealing with authentication and rate-limiting. The actual business logic resides in the connected APIs (including all responsibilities for getting all necessary dependent data).

We lost some features along the way (the mentioned fields / user_fields being one of the), but this change allowed teams to break out of the public API conventions (if they wanted to) and get rid of sharing APIs with external consumers. Some teams experimented with new forms of APIs, screen based ones. We didn’t call it that way but I think later the same idea was coined Backends For Frontends or just BFF. The idea with BFF in the mobile case being that request coordination closer to the APIs reduces the likelihood of partial results and that performance shortcomings could be easier addressed in the backend.

In general this change was perceived well at the time. But trouble was already showing up on the horizon. This change was a double edged sword. Using different APIs with different concepts was not always considered as a win by mobile developers. Turns out they actually like the consistency the old public API was giving them. Even worse, since now everyone was building APIs (mostly in untyped languages), even more inconsistencies started to creep in that drove some people nuts. For example dates in one API were expressed as iso8601 strings, in a different one as seconds from epoc and in a third one as a JSON object with day,month, etc fields. Also screen based APIs are a lot less long lived (at least in the experience I gathered at XING). A next version of the mobile application might have completely different requirements for the screen and since you can’t (or don’t want to) shut the old version down (since some people are still using it), now a backend team is in the unfortunate situation to handle multiple versions of these screen APIs.

Last but not least, let’s admit it, programming in a distributed environment is quite a bit harder than in a monolithic application. There’s a reason why the first rule of distribution is “Don’t distribute”. Getting your mobile API to be robust and perform well in a distributed setting requires often quite a bit of thinking about failure modes and how to deal with them. Over the years I’ve seen them all:

- Huge wait time and exhausted request pools because somebody was having a 10 second timeout somewhere on a dependency that was having some issues

- An API that was so well crafted that it managed to produce internally 1k requests on a single request (when actually <10 would have been sufficient)

- APIs that simply ran into a 500 sitation whenever one dependency couldn’t be reached

The list can probably go further. The jump into this kind of architecture is not easy and definitely comes with a cost associated.

It makes me even more chuckle seeing some people on the internet advocating micro-service architecture (that shares similar traits) to small teams when starting their app. Good luck my friends, good luck.

2016

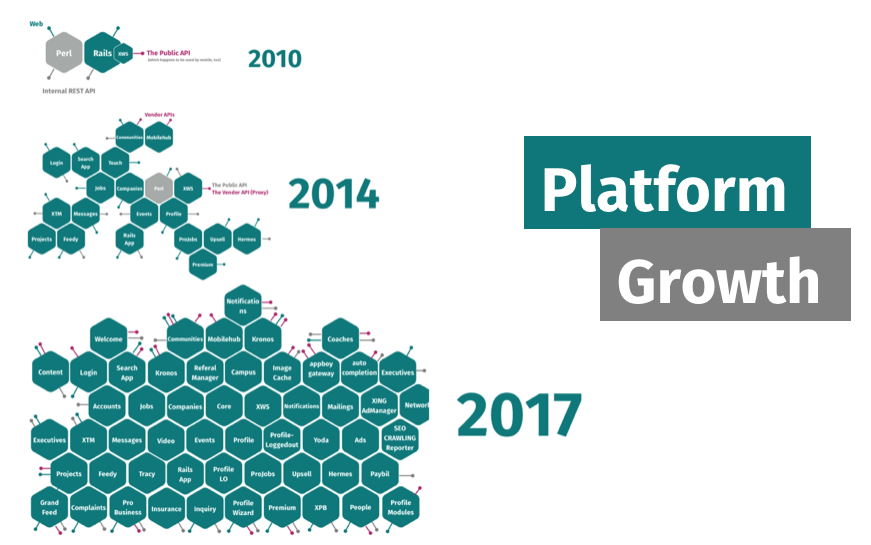

During 2016 more interesting stuff happened. The quick fixes outlined above allowed us to parallelize our API development and with that our mobile development quite a bit. And we grew as an organization a lot. And when I say a lot, I mean it. Just look at the following picture.

Its from a presentation I did in 2017, but the situation wasn’t much different already in 2016. Together with the growth, the complexities associated with our API quick fix noticeably caused more and more pain in our organization. The general theme emerged that it’s too difficult for frontend colleagues to develop on our platform and we’re loosing development speed because of that (which was later also backed up by an internal survey we did).

Also React became a thing (pushed by our colleagues from the Frontend Architecture department) and with that teams needed to support yet another breed of APIs. I was part of the revamp project for XINGs messages section at the time. Internally we call it the “messenger”. Its web version was one of the first larger projects written in React at XING. What we realized somewhere mid in the project is that we basically were building pretty much the same APIs for mobile and the web, but due to some differences on how they needed to integrate with the rest of the platform, we had to expose them twice: Once for mobile, once for web. What a bummer :-/

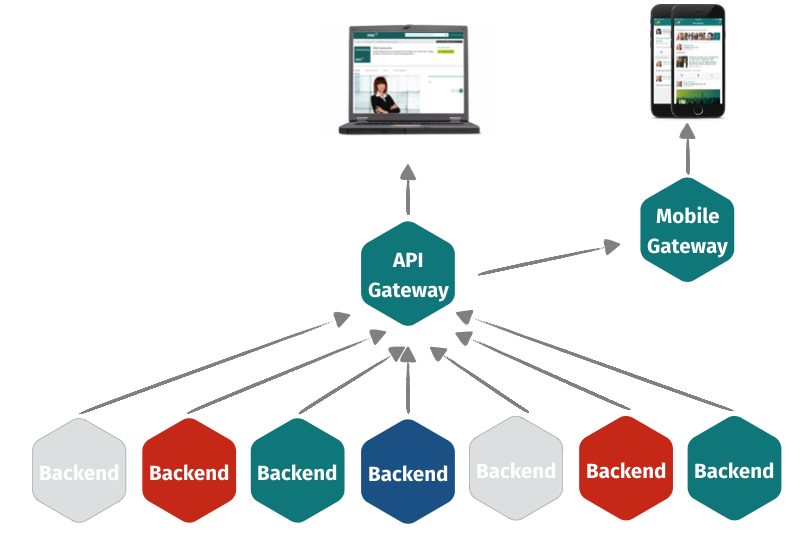

These two things in combination were the last drops that were necessary to convince us that we needed to do something more radical about the API topic and a new project was started. This eventually became XING One, the project and XING One the application which I want to talk about in more detail in this series.

Our requirements

This was probably the longest prologue I’ve ever written for a blog post. I hope I didn’t lose you on the way. What I hopefully managed to convey is the steps and missteps we made with our API and what impact it had on the organization as a whole as it grew.

When we were gathering requirements for our new project, one thing became very clear: We wanted the new solution to have the good properties of our previous ones, while having less of their downsides.

To give you an idea what that meant, we figured that our target solution should have the following properties. It should …

- eliminate the need to write different APIs for mobile and web

- integrate well with our existing internal APIs and internal API conventions

- have a very clear separation of business logic and the other infrastructure concerns, where the business logic resides in backend APIs and the infrastructure is almost 100% free of business logic

- allow the domain teams to be more agile with their APIs by making more information available about who is using what and allowing more flexibility in exposing content

- improve consistency in the whole API

- free our frontend developers from a lot of the request coordination ceremony

- free our backend developers from a lot of response coordination ceremony when assembling responses

- ideally be build around an existing standard with available tools that our developers could leverage

- be easy to extend and teach

- have a top notch development experience

The picture that was forming in our head as a goal looked like this:

So why GraphQL?

I still remember the first wave of GraphQL talks that were coming out in 2015. They weren’t showing much code at the time, but I remember thinking: “Jeeez, this might be it”, “Hey that almost sounds like they had similar problems” or “I bet this could develop into something that might be super helpful to fix our API issues”.

If you go through the desired characteristics, some obviously needed some creativity from us, but others were already solved by how GraphQL was conceptually working.

- The idea that the server exposes a type system greatly helps with the consistency issue

- The introspection capabilities form the basis for top notch tools

- Those in turn lead to a first class development experience

- Explicit queries against the type system improve the insights on the backend side about who is using what by a significant margin

- The setup that

Lee Byron,Dan SchaferandNick Schrockwere showing in their early presentations was also an API gateway, where the logic resided in the underlying APIs. Exactly The separation we wanted to have - The server takes care of a lot of the request coordination aspects that formerly developers needed to figure out

- It can fetch many different things in a single

GraphQLquery (latency optimization) - It only gives you back what you requested (bandwidth optimization)

- Its semantics are clearly defined in a specification that’s openly available, so

GraphQLprobably wouldn’t stay particularly tied to the technology stack of the reference implementation

For the rest, we thought we could probably fill in the blanks and make it somehow work. At the end of 2016 first glimpses of SDL, the Schema Definition Language, showed up and we decided to make a lofty goal: This is how we wanted the glue code between our infrastructure and the underlying APIs to look like. The people that would eventually work with our system shouldn’t have to learn the programming language in which we would develop the infrastructure in. We would have to extend the format for that to work, but we were highly energetic and committed to figure that out.

But before we were to start this technological adventure, I felt that it was necessary to do some additional non technical steps: Basically setting this project up for success in the organization.

How exactly I approached this is a topic for the next entry in the series. Hope you enjoyed this. See you next time around!!!