Our GraphQL learnings and observations

A belated happy new year everyone! I hope everyone of you had a good start into the new year. Todays post is going to be of a different kind compared to the rest of the the series so far. In the last posts I talked in depth about the “why?”, the initial project decisions and the preparations we took to ensure that we’d be able to deliver on our promise. But I haven’t yet talked about our actual experience of introducing GraphQL into our organization.

At the end of the first year (2017) our initiative was already seen as a success and it continued to thrive in 2018 (though slower than in 2017, mostly for reasons that were outside of our control). Most of the benefits we expected from GraphQL turned out to be true. It’s quite eye opening to see colleagues play with GraphiQL (or later GraphQL Playground) for the first time. Pretty much all of them instantly realize the (positive) impact this could have one their work. Some also instantly get that GraphQL has an impact on collaboration between the various disciplines.

But it’s not all roses. We definitely struggled in some areas. In 2018 you can find an ocean full of resources about why GraphQL “is the new sexy”, “superior to REST”, “to REST what REST was to SOAP” and in general “the best next thing after slided bread”. In order to have a meaningful discussion about a technology though, I believe that we also need openly talk about unexpected outcomes, the mistakes we make introducing new technology like GraphQL and also areas where maybe room for improvement for such a technology exists. Only then can we have a more nuanced view on a piece of technology.

Some of the things that I’m going to reflect about today are likely the result of a combination of multiple factors. Our approach, our culture, our setup and other influences played into it. To give you some context about the company I’m working in (and that is worth understanding before going into the individual points):

- My employer has roughly 1,3k employees of which ~300+ are developers

- Of these to my knowledge roughly 70+ are native mobile developers

- For the rest I don’t have concrete numbers, but my feeling is that it’s roughly 2/3 backend developers and 1/3 web frontend developers.

- Most of the engineering teams are setup to build all representations of their product (backend, ios, android & web)

- In comparison the teams that are dealing with platform topics are fairly small.

- The system architecture team (which primarily is concerned with running our

PAASplatform based onKubernetesthese days) is ~10 people. - My team that was pushing the

GraphQLinitiative counts 4 people (including myself and we also had to maintain our OAuth gateway on the sidelines).

- The system architecture team (which primarily is concerned with running our

- In general our engineering organization tries to give a lot of freedom and autonomy to individual product teams, but in general shields them from platform related work. As a consequence there’s always the lingering pressure for platform related teams to find ways to do their work without interrupting or even blocking product teams and as a consequence a lot of the larger technology initiatives by their nature need to be incremental and non-blocking in how they’re rolled out.

That being out of the way, let’s dive into our learnings and observations:

1. Expectations on GraphQL vary dramatically between web and native mobile developers

Have you ever called into a GraphQL service by hand, without some GraphQL specific tooling? Like with curl or fetch? If you’ve tried that and have understood the format that a GraphQL server expects, then you realize that everyone who is able to do a REST call is also able to interact with a GraphQL server. They are not too far apart. Sure, the error handling differs significantly, but the general mechanics of obtaining data a very close.

This enabled for us a more or less straight forward iterative rollout plan:

- Get rid of the

BFFsand useGraphQLto talk to the platform instead. - In case there’s value seen from the frontend teams, move higher into the client stack.

Always assuming that we need to manage the risk of GraphQL turning out to be such a great fit for our landscape. We tried to be lean and adaptive. So much for the theory, now comes the practice part.

Our mobile developers pretty did exactly that. It kinda seems logical now, looking back at the last two years, since a lot of our motivation came from mobile challenges. That group treated GraphQL as a drop-in replacement for REST that freed them from a lot of the request coordination logic. They had some gripes with error handling (more on that later) and the available native libraries (both mobile teams opted against using the available Apollo library, because they deemed them not ready yet), but all I think they were pretty happy with our proposition.

On the web side, things became slightly interesting though. React had already been in place for quite a while as the default client side library, together with Redux as the client side state management solution. BFFs were the norm and supplied the frontend with data. Our GraphQL gateway would make these BFFs obsolete. Not so different to the mobile side, or so we assumed.

In retrospect this assumption is one of the larger mistakes that I personally made.

Let’s say it this way, this idea created quite a bit of friction between the API team pushing the GraphQL topic and the team responsible for the frontend architecture. It turns out for them, GraphQL wasn’t only about an API. It was a whole new way to build applications end-to-end (basically API + client side state management + self contained React components that specify their data requirements via co-located GraphQL queries and fragments). And they wanted to have all of that experience immediately. All of the great Apollo talks and demos in that area certainly also didn’t make it easier for us.

The only problem though was this: We lacked the client side experience and the frontend colleagues lacked the resources / time to properly accompany this. Which led to introducing Apollo for example at a later point and a time where we significantly lacked guidance on how to bring all the pieces together in the frontend. This resulted in some surprises, for instance in the client side caching behavior which we initially weren’t aware of.

The point to take away from this is that you should plan and setup your GraphQL introduction end to end, with all necessary client resources available. While mobile developers were fine with an incremental adoption, trying to follow the same approach on the web created friction for us. The GraphQL buzz today primarily happens on the web side and in the Javascript world. With that expectations of what GraphQL is able to deliver differ dramatically from their mobile counterparts.

It’s a bit ironic, when you know a bit of the history of

GraphQL. If you trace back theGraphQLstory to its origins withinHTML5approach within their mobile applications. When the decision was made to switch the strategy to go all-in on native development instead of web technology, it was a combination of “having a great, working concept” and “being at the right spot, at the right time”. They pretty much created the blueprint for things to come.GraphQLdidn’t start out on the web or evenJavascriptside. Only when they came to the conclusion that “this could really be a thing”, they created the spec and the reference implementation inJavascript. But this happened at a later point.In case you wondering: In 2017 I sat next to Dan Schaefer in the cab on the way to the speakers dinner for the

GraphQL EUconference and had the chance to pester him with all sorts of questions. Dan is one of the originalGraphQLcreators (besides Nick Schrock and Lee Byron).

2. Client libraries weren’t on par when we started

I hinted it in the first point, if you’re going to build not only for web but also for the native platforms, you have to be aware that there is quite a difference in breadth and depth of available documentation for those different platforms. When we started in early 2017 documentation for the native client libraries was basically not existent. The Android library was in a very early alpha state, the iOS version was a bit (but not much) ahead.

Both of our mobile teams looked at them in 2017 and eventually decided to roll their own tooling. This made the integration into our OAuth 2.0 flow and the rest of the existing application easier, but obviously also comes with a cost associated. Many of cooler later additions on the client side libraries can’t be found in our native mobile applications.

I guess it’s one of the prices you often need to pay as an early adopter. Just looking at Github today, it looks like the libraries have nicely developed in the meantime. If faced with a similar choice today, the result would probably be different.

3. All client developers struggled with error-handling and partial results

In November 2017 I gave a talk about our GraphQL experience in Munich while visiting Autoscout 24. One thing that stuck with me from the following Q&A is that one of their Lead Engineers was noticeably taken aback by my assessment that client engineers struggle with error handling and partial responses more than expected. From his point of view the partial responses were one of the reasons to use GraphQL and he was heavily advocating that on their sided. And now I came along and talked about how our frontend colleagues struggle to make the shift there.

The interesting thing here is that I don’t even have a very different personal opinion. I think partial errors are great. That the server is able to give you something back in case he can’t resolve all of the data is actually a great premise to me. Especially if your GraphQL server (like ours) is a gateway that is remotely talking to other services and the fallacies of distributed computing come into play. Partial results reflect the reality of a distributed platform much better than the normal binary “worked” or “didn’t work” approach (when in the latter case maybe just a tiny portion of the data couldn’t be resolved).

But at least in our company I made the observation that frontend developers aren’t so fond of this changed behavior initially and for some of them it takes quite a while to accept and wrap their head around this. Just to give you one example: I’ve seen mobile developers that were already working for more than a year with GraphQL and tried to talk their backend colleagues into making the schema super strict with mandatory fields for fields that might fail everywhere. The intent being that constraint violations would bubble up and they got their beloved binary behavior again. In the end we talked them out of that. My team 2 years in is still consulting product teams to think about how to model their schema in a way so that it’s usable in the presence of partial errors.

Things take a while to stick. Especially if you’re coming from a REST setup and your work affects many people, I would try to clarify this aspect as one of the earlier topics.

4. Even though GraphQL documentation is great, onboard carefully

At the start of 2017, if you wanted to understand how GraphQL worked and what kind of assumptions it did, there were already great resources out there, especially graphql.org. We pointed the first team we worked with towards these resources. Needless to say, it turned out that this wasn’t enough. Otherwise I wouldn’t be writing about this now :)

Great documentation is awesome, for the case where people actually bother to read it. At least half of the people you typically meet also do this. The other side immediately goes into exploration mode and tries to build something, without going into the documentation. And out of that group from my experience one half reads the documentation when it encounters problems. The other half doesn’t even do that. That group usually approached us in frustration about why “this” and “that” wasn’t working as they expected.

To give you again some examples:

- I already talked about the mobile engineers and their desired behavior for partial responses

- We were approached by one backend engineer that worked under the assumption that you could send multiple queries simultaneously to the

GraphQLserver and the server would magically optimize these multipleGraphQLqueries into a perfect execution scheme. Needless to say that our server only accepts oneGraphQLquery at the moment and the only reason why we accept anArrayas an input is that we speculated that at some point batch operations would land in the spec (which is a completely different thing and also hasn’t happened yet) - Another frontend colleague who took query co-location to the maximum with every

Reactcomponent having his ownGraphQLquery, apparently wasn’t aware of the solution using fragments and was vividly arguing that ourGraphQLserver was frontend-unfriendly and unusable if we didn’t support Apollos batch handling.

From this experience we changed our rollout scheme dramatically. We developed a full 2 day onboarding program that alternated between theoretical content and lots and lots of practical exercises, that are close to what engineers have to build in the final product. And we switched our initiative into a mode that resembles the typical, invite-only private beta you’d normally encounter on producthunt. The assumption here being that you have to mange onboarding with a limit so that you can learn with a limited surface for errors and adapt for the following teams.

In one of the earlier parts of the series I talked about that we treated everything as an MVP: The implemented server, the process and the documentation. Onboarding was a logical addition to this and we continue to do these workshops even in 2019.

5. GraphQL type system feels (sometimes) too basic

When working with a large group of people on a schema, I think GraphQL is lacking some basic things in the schema. I think this is independent of whether you work with a single schema or use some form of schema-stitching.

The first one that comes to mind is the simple concept of namespaces. A “profile” in one domain might be something completely different to a “profile” in another domain. You might want to call both “profile”. As of now, if you want to have both of them in a schema, you need to make their names unique, usually by prefixing their name somehow. For instance having a CompanyProfile and a MemberProfile. That’s also what we do currently.

I know the argument that existing tools do already a good job to identify conflicts, but I would prefer having an explicit concept of namespaces that also works without some form of extra tool or linter, so that we could also have Members::Profile and Companies::Profile.

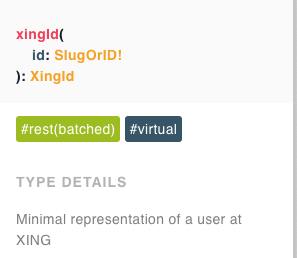

Another aspect that I find lacking in the type system of GraphQL is a way to express the behavior of fields somehow. For example: If you have multiple fields coming from different sources, there’s likely a different “cost” associated to them and I would like to express this also for tools and inside the documentation. Sangria already has this nice concept of FieldTags that you can attach to a GraphQL field. You can think of them similarly to .NET attributes or Javas annotations. For our system we’ve figured out a way to signify which FieldTags are documentation relevant and automatically show them inside GraphQL playground. The goal being that you have a higher value documentation of the behavior of a field.

Here’s one example for this:

This shows the documentation of a field that is backed by a REST API, where multiple occurrences of this are batched together (@rest(batched)) and that this particular field is not requested from the backend when the parent is resolved (@virtual). We “faked” this by prefixing the normal documentation and patching GraphQL Playground to show the tags in a nicer way using colors and explanatory tool-tips.

But this is a duck-tape solution and again I would prefer to have a real answer similar to this for GraphQL. I think the logical solution for this would be to make server side directives part of the exposed schema, but I’m not aware of any plans to add this.

6. GraphQL spec lacks a pagination abstraction

Sooner or later as an application developer you will encounter the topic of pagination in your schema. The GraphQL spec is completely agnostic when it comes to the pagination topic.

It’s not like there isn’t a fitting spec available. The Relay Cursor Connection Specification pretty much exists since the early days of GraphQL, but separately from the GraphQL spec. Prominent GraphQL APIs like Github and Shopify do make use of it. We also use it more and more (both for real cursors and as an adapter around limit and offset based APIs).

Not having a default pagination abstraction obviously gives some flexibility and adaptability for GraphQL itself, but I can’t help to think that GraphQL could benefit from having a default abstraction for this out of the box. If there was an explicit concept, tooling could make better use of this and also frontend components would have a more standardized notion of pages of data.

7. Don’t be naive with file uploads

Somewhere in the middle of 2017 the topic of file uploads came up. We did the simplest possible solution: Tunneling the binary file as a Base64 encoded blob though our GraphQL mutation. That works, but is in general a very bad idea. You could even call it naive.

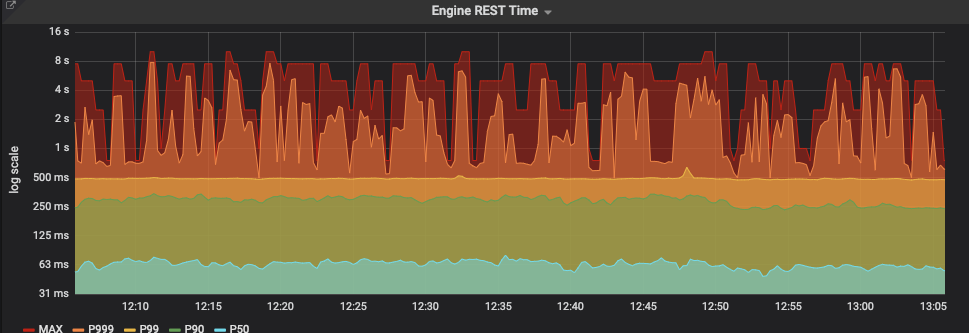

Take a look at the following dashboard. Guess where most of the P999 and MAX numbers are coming from :-(

Needless to say, this clogs throughput on the gateway side and decreases the capability to properly monitor the system. Even worse, you run into situations where the frontend times out, but the upload has reached the servers and is actually being processed (only very slowly).

We’re in the process of migrating away from this quick-fix to a separate upload service based on tus. In the new setup the GraphQL schema only provides the means to secure an upload slot and the upload is living completely outside of GraphQL.

I can only advice you not repeat this mistake and keep uploads separately where possible.

8. We struggled with our mutation design

Oh mutations, another unexpected headache. You see GraphQL servers execute hierarchically and sub-selections only apply when the parent resolver was successful.

The first version of mutations was pretty simple in that sense that for successful REST calls underneath, we expanded the selection and where they failed, we added an entry for them as error extensions into the global errors collection. Straight forward, or so we thought.

Turns out that the first wave of mobile developers hated the extra effort that they needed to do when they wanted to access this error information. And we changed the implementation to please them.

Our final version of mutations basically contained an explicit model of the error response in the schema. Mutations pretty much nowadays look like this:

type ContentArticleMutationResult @mutationResult {

success: ContentArticleInterface

error: ContentError

}

The extra @mutationResult directive is necessary to enable an exclusive-or behavior. So it’s always one of the fields filled but never all of them. There’s good about this design, since it also enables you to model your errors explicitly and you can also see errors in your schema now.

On the other hand, we broke two basic things that are worth mentioning:

- It doesn’t follow the normal hierarchical execution model of

GraphQL - It also is not symmetric to queries anymore

We have some few noteworthy occurrences where for queries, the same team that heavily objected our first mutation design is now more or less perfectly fine with reading out of the errors collection in case a query failed. You only realize this in retrospect, but to me this indicates that we as an API team maybe gave in to early in order in this area of GraphQL to please our customers.

09. Retrofitting into an existing APM solution is easier than you think

When the question comes up today how you would monitor performance and health of your GraphQL application,

you’ll likely eventually end up with Apollos toolsuite. The company has done a good job capturing the momentum with their former Apollo Engine product which was recently superseded by the Apollo Platform.

At the start of 2017, when we started. Apollo wasn’t there yet though and a bit later we also didn’t feel fully confident to put such a young product in front of our platform. So we rolled our own integration into the existing monitoring solutions used at my employer:

- Logjam for application performance monitoring and request tracing

- Grafana, Prometheus and Prometheus alertmanager for filling in the blanks where we either wanted or needed more information that couldn’t easily be expressed in

Logjam

The effort in making this happen was manageable. People that came into contact with our GraphQL gateway could continue to use the tools they were already familiar with. And of course, if were ever wanted to do something special, we could bend our tooling to our will. To give you some ideas how it looks:

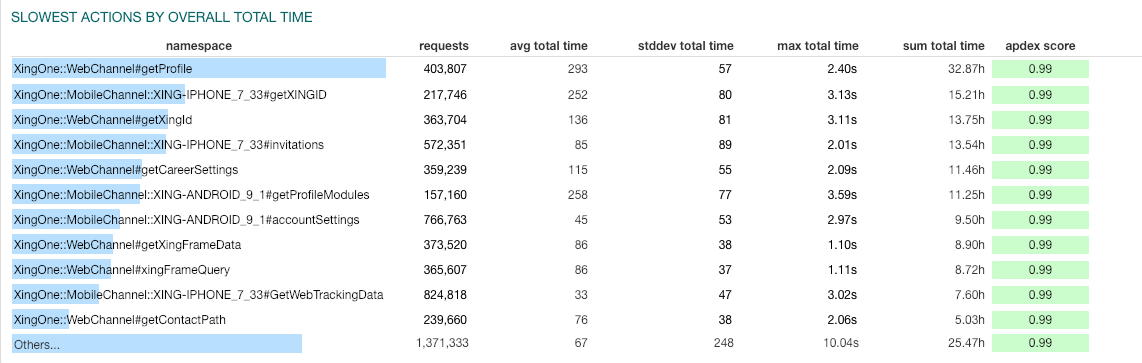

Here’s a dashboard that shows the slowest GraphQL queries in Logjam

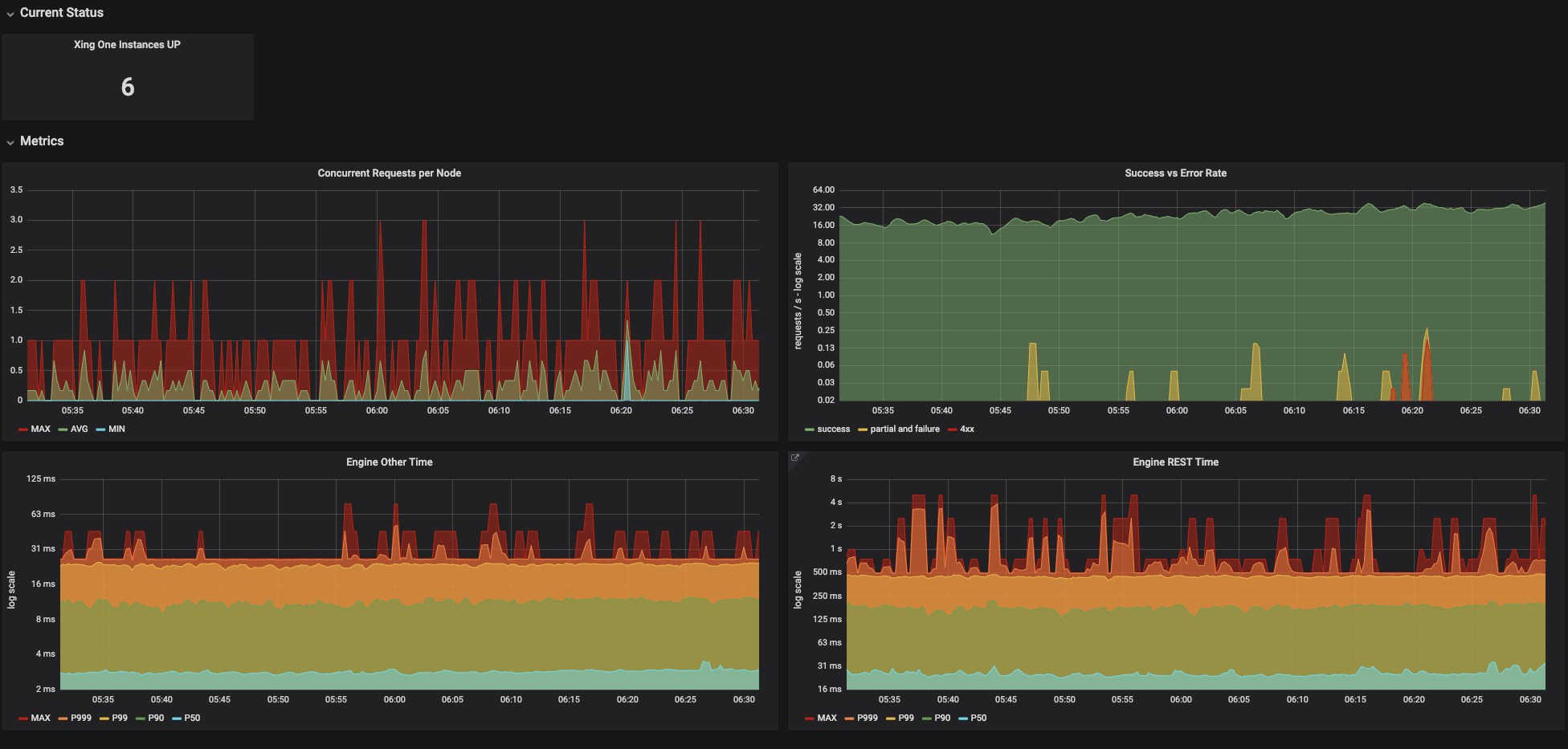

Here’s our golden dashboard that we use for system wide overviews

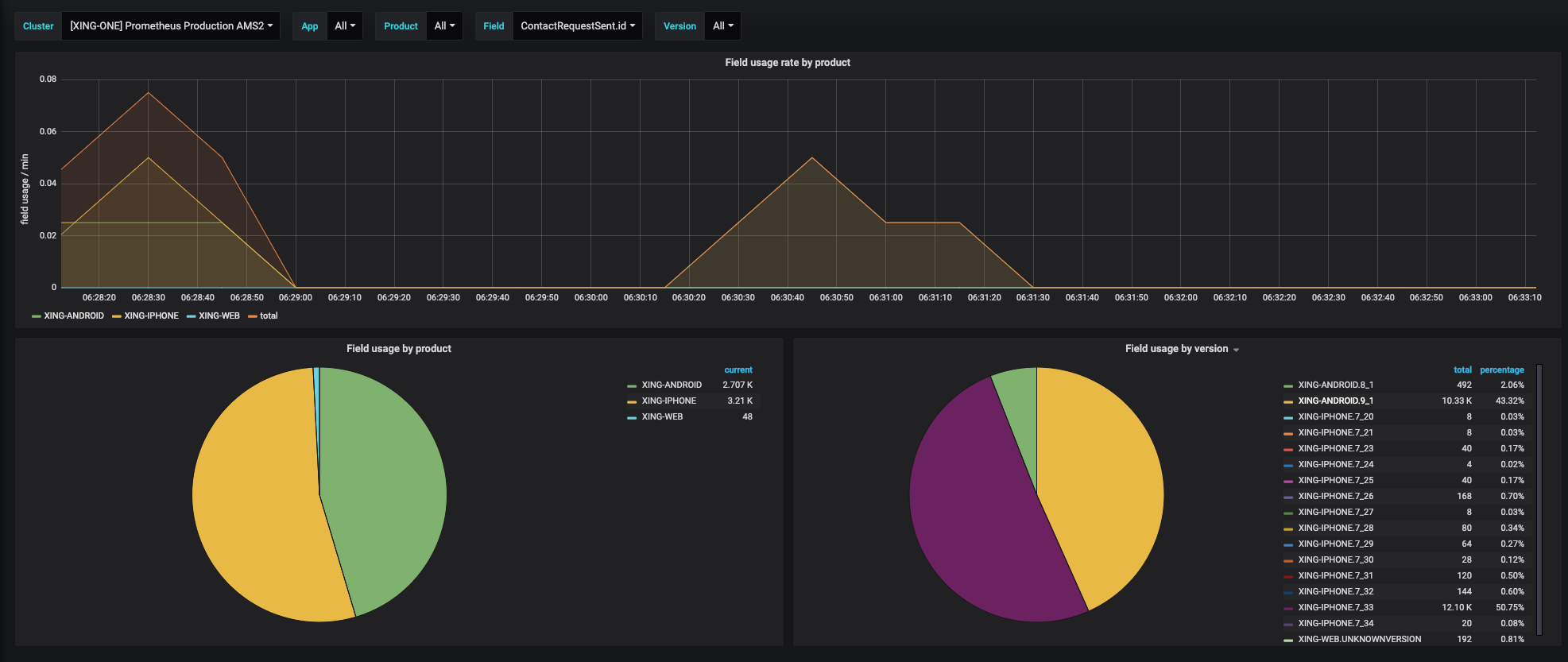

Here’s another view into the dashboard we use for field usage tracking

And we’ve got many more, for example for the internal REST client and also the JVM system metrics.

There’s a lot of heated discussion about monitoring tools in our company at the moment and Apollo took the GraphQL APM space by storm in the last two years, but we found this way both feasible and practical. If there’s a killer feature in Apollo that we direly want and aren’t able to replicate, then we’d probably have a second look at the Apollo Platform, but based on the experience of the last two years, we don’t feel like we need to.

10. Schema-first is only half of the story

When I saw the first bits of SDL I immediately liked the idea. We had the challenge at our company that we operate in a polyglot environment and we specifically didn’t want to teach the programming language the GraphQL server was written in to everyone who contributing to it. On top of that we were searching for a way to have a meaningful discussion about the schema without going too much into the mechanics of it, a good abstraction so to speak. SDL looked like the perfect fit.

And to a certain degree it is. Almost everyone we worked with, be it backend engineer or frontend-engineer, native or web focused, all of them were able to pick up SDL in very short time. However in all of the available GraphQL servers I know, the declarative part ends once you hit the resolvers and you’re forced to learn the programming language the server is implemented in again.

If you want to have a fully declarative approach, you need to fill in the resolver portion. And this doesn’t come cheap. Most of the engineering work we’ve done in the last year was basically about making end-to-end SDL a reality and work on real product problems.

Too be clear we’re pretty happy with our results. With our system, we’re able to push an executable schema into the server within seconds, making it super smooth to work with. But we’ve also diverged from the typical GraphQL approach quite a bit. The end of this is not foreseeable and the future will tell how good we’ll fare with our approach (compared to the alternatives).

In case you’re curious: My co-worker David gave an excellent talk about our SDL approach at last years GraphQL EU conference.

Conclusion

This post started out as the summary of what we learned in the first year with GraphQL. Somewhere in the first half, it somehow reshaped into overall learnings so far. Things usually overlap a bit time-wise and I thought the post is probably more valuable if I share all of our learnings.

I hope I could give you a bit “food for thought” when it comes to GraphQL. Like I said in the introduction, my feeling is that we already have enough success stories out there and need to get a more rounded picture.

Don’t get me wrong. GraphQL is an amazing technology and we enjoy working with it every day. But there’s no free lunch, especially when you introduce GraphQL into an existing product organization without a large rewrite.

See you next time around!

:wq