Choosing the right technology for XING One

Figuring out what technology to use for a large scale, long term project is never an easy feat. 8 years ago XING was pretty much only using Perl and Ruby (on Rails) in the backend. In 2017 we had plenty of options to choose from: Java, Scala, Elixir, PHP, Javascript and Ruby. Most of them offer GraphQL implementations.

So how do you skin that cat?

First of all, I made the conscious decision not to make my personal skills or the widespread availability of knowhow within XING a trumping factor in the decision.

I had successfully delivered products and projects in Ruby and Elixir within XING and a longer history with C# before that. I even had done Martin Oderskys Functional Programming Principles in Scala course on Coursera in my free-time one or two years prior to the project. All in all, I was confident enough that I would manage to get proficient enough to deliver in any programming language if I really had to.

I also felt that our project shouldn’t be restricted by heritage and that we should pick the best solution for the company with a forward oriented mindset. If I were to base the decision predominantly on the availability of knowhow within XING, the answer would involuntarily lead me to Ruby, which is still the most used technology stack within our company in 2018. But I had my doubts whether Ruby would be a good implementation choice for our proxy.

“Opinions”, “doubts”, let’s be honest, we’re all more or less biased one way or another. I definitely know I was biased when it came to certain technologies I had used before (at the time I was a heavy advocate for Elixir for example). But I thought it was a good idea to counter balance that bias through a more transparent and structured selection process.

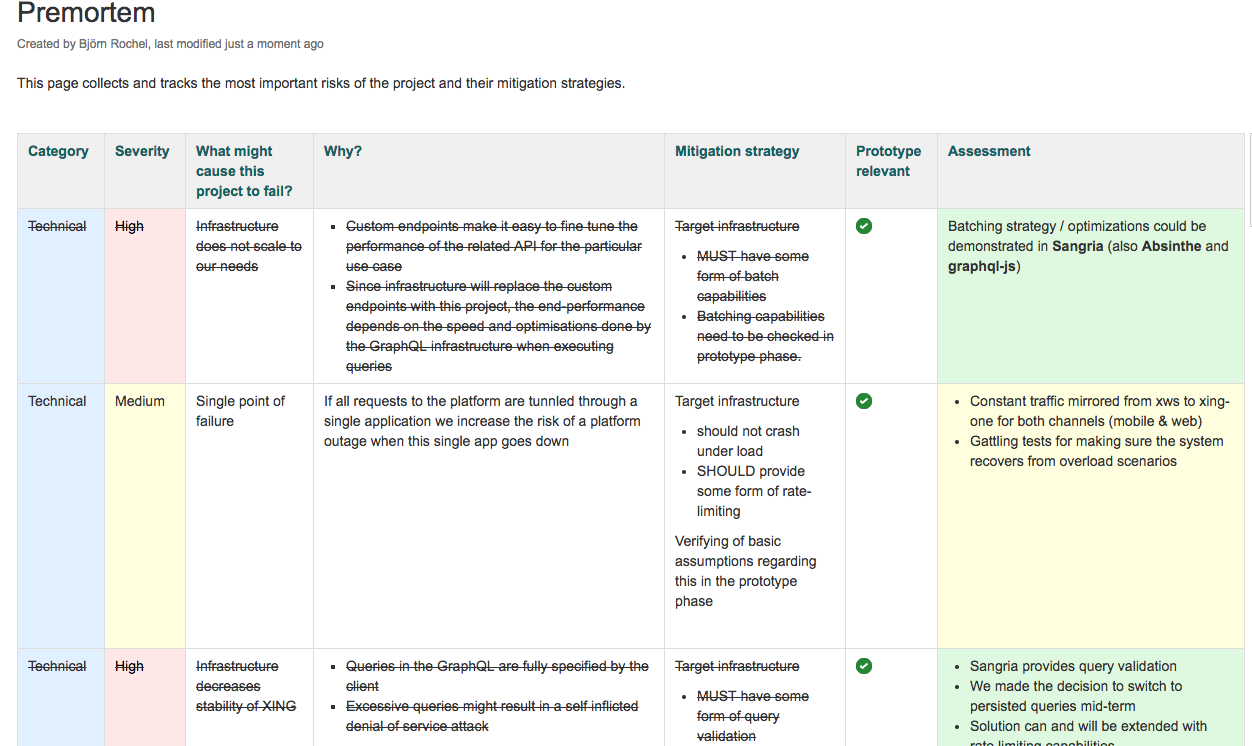

Enter the Premortem

Some months prior, I had read Decisive by Chip and Dan Heath and one of the tools that was described in there, was a Premortem. In a nutshell a Premortem is the hypothetical opposite of a Postmortem: You don’t analyze the failure after the fact, but instead hypothesize what could turn the project into a spectacular failure and then ask the simple questions of “Why?” and “What would I have done about it, if I had known earlier?”.

Done collaboratively it allows you to surface risk and brainstorm detection and mitigation strategies from multiple viewpoints in the earlier phases of an initiative. Those phases when you can still do something about it. Of course this doesn’t rule out Black Swans, the unknown unknowns, but it certainly helps to form the right mindset: To be proactive, instead of reactive. Since it was only me back then, I mostly used my boss as the sparring partner for the Premortem, which also helped me to understand the project from a management perspective better.

We did another larger

Premortemfor our rollout strategy into the company. I’ll show this in a separate blog post, because this one contained one additional element that I find fascinating: Tripwires, or how you would know when something is actually starting to happen.

You don’t need some sophisticated tech for this. Our first version was an Excel sheet that was later moved to Confluence for documentation purposes. To give you some general idea how this might look like, ours kinda looked like this (even though this is just an excerpt, the real one is multiple pages long):

The checklist

You probably know this famous quote from Yogi Berra: “In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is.”. During the Premortem phase we developed strong hunch that the technology decision for XING One needed to contain some decent amount of hands-on coding in the respective options.

Because of that we decided to do something that was unusual and uncommon for technology projects at XING (and to my knowledge still is): We spend the first 1,5 months actually implementing a throwaway prototype of our idea in all the relevant technologies

We extracted all gaps of knowledge and risks we surfaced in the Premortem that could be validated in the prototyping phase into a simple checklist. You can see those in the screenshot above in the “Prototype relevant” column.

In the end the shortlist of candidates for our prototyping phase were:

Rubywith graphql-rubyJavascriptwith the graphql-js reference implementationElixirwith absinthe- and

Scalawith Sangria

How did we end up with those? The reason for this is two-fold. First, we made a pre-requisite that for every technology stack option we would require at least some minimal in-house production experience. This was primarily intended as a fallback scenario when our problem solving or troubleshooting skills hit an impasse.

Second, we didn’t want to have deep integration into our monitoring and deployment infrastructure in the critical project path. (I was just coming of a stint in our messenger product where I spent 1,5 months on building an integration with our in-house messaging system for Elixir)

Our checklist contained an example schema, 3 different GraphQL queries and 1 GraphQL mutation to execute against the server. That was primarily for observing and comparing the execution behavior, but also to get a decent understanding how a GraphQL server in general works.

On top of that it contained a whole bunch of other things to investigate:

- Which of our general assumptions about

GraphQLturn out to be false already at this stage? - Does the

GraphQLimplementation tick more like a library or a framework? - How easy is it to customize behavior here and there?

- How good is the documentation?

- How active and inclusive are the maintainers?

- How easy is it to get changes in when necessary?

- As a gut feeling how big is the part that we need to build on top and what was our gut feeling whether we could pull this of?

I wrote the prototypes for Ruby, Scala and Javascript. During the third week of the prototyping phase Alexis Mas joined the project, coming over from a different part of the company. He built the Elixir prototype. And finally I wasn’t alone in this anymore.

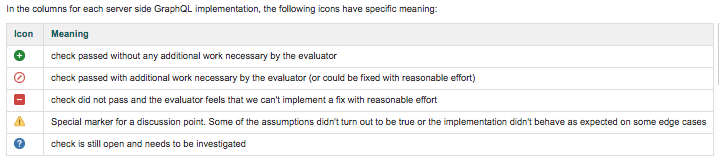

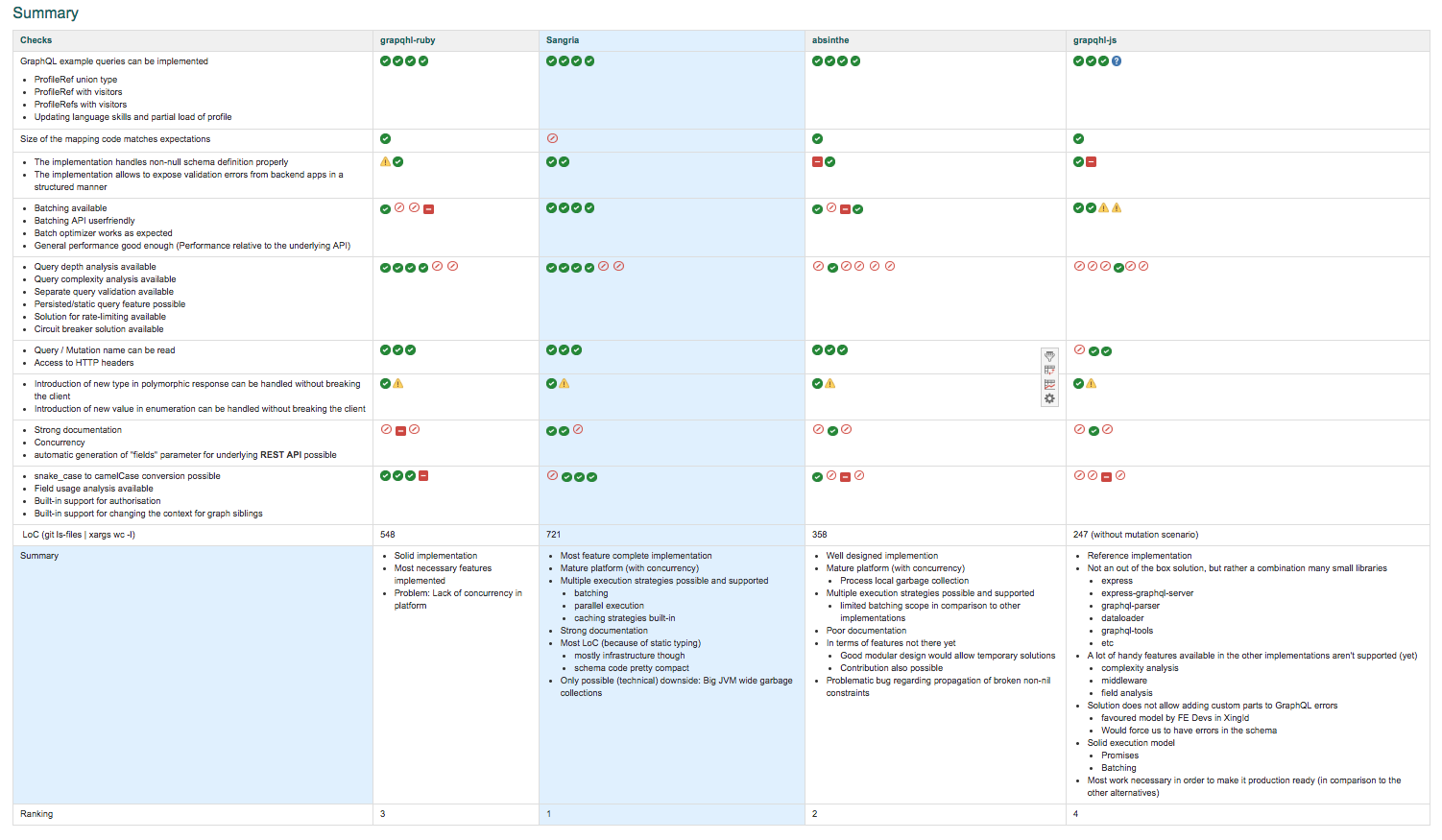

We had planned to use only 1 month for the evaluation. In the end it took us 1,5 months. The net result of the prototyping phase can be seen in the following two pictures. The symbols you see in the checklist follow the following scheme:

Please note that your looking at the summary overview. Internally a longer descriptive version of this still exists in the documentation of the project.

I’m pretty certain that our conclusions might be not be shared by some folks out there. We tried hard to make them somewhat transparent and comprehensible, but they still contain subjective impressions. But hey, companies are different and not everyone might arrive at the same conclusions coming from different contexts.

Please also note that we were doing this evaluation in February 2017. Work on

apollo-serverhad just begun. Re-doing the evaluation today might result in a slightly different ranking. I doubt though, that the top spot for us would be different.

Why we chose Sangria

In the end Sangria, the Scala solution, turned out to be our favorite. It collected many plus points during the prototyping phase:

- The documentation was top-notch

- Conceptually, it quacked more like a library than a framework. As a consequence it was fairly easy to change and extend the behavior of the

GraphQLengine. Even better, a lot of those extension points also had high quality documentation. - The concurrency capabilities of the platform looked like a good fit for our proxy scenario and

Sangriaprovided a lot of interesting batching and execution options out of the box. - Some features were already implemented in

Sangriathat were still being discussed in theGraphQLcommunity at the time and lacking in some of the other implementations (for instance the complexity analysis or SDL based schema materialization)

Last but not least, I had a good gut feeling about Sangria as an open source project itself. In the short contacts and brief online interactions I had with its maintainer Oleg Ilyenko I was amazed how knowledgable and at the same time humble and helpful he was. My impression was that if we would ever run into dead-ends with Sangrias code, for most scenarios we wouldn’t have to run a fork, simply because of Sangrias extensibility. And for the other cases where this wasn’t true, we could work with him to bring the necessary changes to Sangria. This gut feeling turned out to be true multiple times and I think this is also one of the reasons for the success of Sangria and why especially bigger companies seem to be betting on it. I’ll write a bit more about that aspect in future posts, promised!

Choosing Sangria is one of those decisions that I’ve never regretted. I never even once looked back thinking “This would be so much easier, better or cooler in XYZ”. We’re still happy with that choice, even after roughly 1,5 years of working with it. And you will see in the following posts, that our usage of Sangria is, well, a bit unconventional (to say the least).

Now, you might remember from the last post, that we were not planning to build our GraphQL infrastructure in isolation. Instead were gearing up to build a new version of the profile with the respective product team. There was only one tiny complication: In March 2017, not a single line of production code for our infrastructure was yet written (since we archived the prototypes). On top, a bit more than one week of Scala coding also did not magically turn us into Scala professionals. Obviously we had some additional stuff to figure out for our next steps. And we had to figure them out fast.

In the next post I will talk a bit about the initial game plan we derived from the Premortem and prototyping phase. I’ll also outline our ideas for the general design of our GraphQL infrastructure and how we wanted to evolve it over the year. See you next time around!!!

:wq