On AI and Existential Fears

Let me tell you about the dumbest smart thing I’ve recently done.

I needed to update my CV. A normal person would spend an afternoon reformatting bullet points and adding their latest role. Instead, I spent multiple weeks deep-diving into Claude Code to build a full application that ingests reference letters, extracts testimonials using LLMs, and produces a credible CV complete with quotes and skill validations.

An afternoon task turned into weeks of engineering. And I regret nothing — because the CV was never the point. The point was understanding what this technology can actually do when you push it, and what it can’t.

That experience, combined with 2+ years of working with AI coding tools professionally, has left me with a perspective on where software engineering is headed that I think is worth sharing. Not because I have all the answers — none of us do — but because I’ve been through enough of the hype cycle to have some battle scars.

Drinking from the Firehose

A bit of context. I’ve spent the last four years working remotely for a US-based startup. American tech culture has a particular relationship with competitive advantage: if a tool exists that might make you faster, you use it. No hand-wringing about purity. No waiting for consensus.

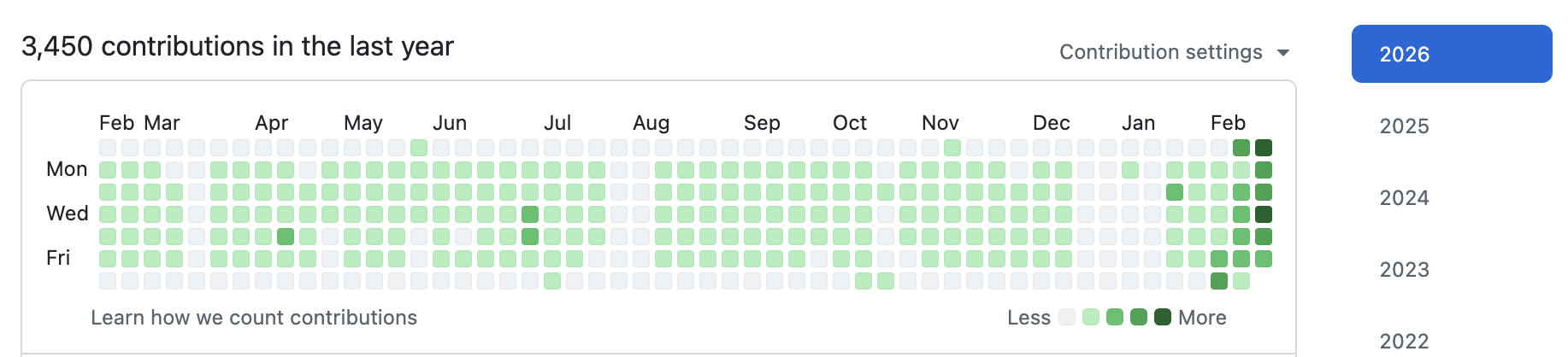

As a result, my organisation went through the full progression: Copilot, then Cursor, then Devin, then Claude and Codex. I watched this evolution happen in real-time — and I watched my own role evolve with it. As an Engineering Manager, I found myself becoming dramatically more hands-on, shipping code on top of my normal leadership responsibilities. My GitHub commit graph tells a story that would have been impossible five years ago.

I’ve been on every stage of the hype cycle with this technology. The initial wonder. The inflated expectations. The disillusionment when it generates confident nonsense. The quiet realisation that it’s genuinely useful when you know how to wield it. I’ve even had the existential crisis — the 3 AM thought of “is my career about to become irrelevant?”

So when Dario Amodei predicted that 90-100% of code would be written by AI by the end of 2025, my initial reaction was unambiguous: full of shit.

The Amodei Prediction, Revisited

We’re past that deadline now. So was he right?

The answer depends entirely on who’s talking and what incentives they have.

Amodei and the creators of Claude Code claim that this is exactly what’s happened inside Anthropic. On social media, you’ll find enthusiastic early adopters sharing similar stories. And I’ll be honest — my own commit graph lends some credibility to a version of that claim. When I’m working with Claude Code, the AI is generating a substantial portion of the raw code output. In that narrow, measurable sense, the prediction isn’t as absurd as it sounded.

But let’s zoom out.

These are still early adopters, not the majority. Most companies are still figuring out what AI-assisted development even means for their workflows, their security posture, their hiring. The enthusiastic voices on social media are a self-selecting sample. And crucially: the people making the boldest claims about AI’s capabilities are the same people selling AI. Amodei is the CEO of a company whose valuation depends on you believing that their technology is transformative. It’s literally his job to say this convincingly.

That doesn’t make him wrong. But it should make you calibrate.

The reality, as I see it: AI-assisted coding is directionally real, genuinely powerful, and already transforming how early adopters work. It is not yet mainstream, not yet well-understood by most organisations, and the narrative is heavily amplified by people with financial stakes in the outcome. Both of these things are true simultaneously.

How This Technology Actually Works — And Why That Matters

Now, let me push back on a common dismissal that I hear from sceptical engineers — one that I’ve caught myself making too.

“It’s just token completion. It’s probabilistic. It doesn’t understand anything.”

This is technically accurate and practically misleading. By that logic, human cognition is “just neurons firing.” Dismissing a system’s capabilities based on its mechanism is a category error. What matters is what it can observably do, not how it does it.

And what current AI models can observably do is impressive. They can reason through architectural tradeoffs. They can refactor across multiple files while maintaining consistency. They can write tests, identify edge cases, and explain complex codebases. These aren’t parlour tricks.

But — and this is the crucial “but” — they also have real, observable limitations that matter enormously for professional software engineering.

The models are trained on publicly available code and documentation. Let me ask you an uncomfortable question: is most publicly available code good? Is most open-source software well-documented? The honest answer is: some of it is excellent, and a vast amount of it isn’t. Models don’t simply replicate the most common patterns — modern training techniques like RLHF help them discriminate quality from noise. But they are fundamentally bounded by what they’ve seen.

And here’s what they haven’t seen much of: your specific system. Your org’s production traffic patterns. Your particular failure modes. The reason that weird workaround exists in the payment service. The implicit assumptions your team makes that have never been written down. AI doesn’t lack intelligence — it lacks situated knowledge.

The Dark Side: Where Expertise Actually Lives

This brings me to what I think is the most underappreciated argument in this entire debate.

The hard part of software engineering has never been writing code on the happy path.

Think about what actually keeps senior engineers up at night. It’s the Fallacies of Distributed Computing. It’s the failure mode that only manifests under specific load patterns at 2 AM on a Saturday. It’s the security vulnerability that exists not in any single line of code, but in the interaction between three services. It’s the observability gap that means you can’t even diagnose the problem when it happens.

There is remarkably little in the public training data that captures how experienced engineers operate software:

- Observability and forensics — How do you instrument a system so you can understand what happened after a 3 AM incident? How do you build dashboards that surface actionable signals instead of noise?

- Scaling — Not the textbook “add more instances” kind. The kind where your database’s query planner makes different decisions at 10x traffic and everything subtly degrades.

- Security — Not the OWASP top 10 that AI can recite. The subtle authentication edge cases, the supply chain risks, the threat models specific to your architecture.

This is the stuff they don’t teach you in tutorials. It’s barely present in documentation. And it’s vanishingly rare in public codebases. This knowledge lives in the heads of experienced engineers, in post-mortem documents buried in private Confluence spaces, in the institutional memory of teams.

Now, I want to be honest here: AI is starting to enter these domains. There are AI-powered observability tools, security scanners, and incident response systems. The gap is real but it’s closing. My argument isn’t that AI will never handle these things — it’s that right now, and for the foreseeable future, this is where human expertise provides the most irreplaceable value.

AI engineering itself isn’t trivial either. It’s telling that the most sought-after course in the US product management world right now is about evaluations — how to measure whether your AI system is actually doing what you think it’s doing. Building reliable AI-powered features requires understanding failure modes, edge cases, and probabilistic behaviour. In other words: it requires engineering expertise.

AI needs an operator.

So Is It Just a Fad? Can We Lean Back?

Absolutely not.

I want to be direct about this, because I think complacency is a bigger risk than panic.

We are seeing the largest shift in software engineering that I’ve witnessed in over 20 years in this industry. This isn’t hyperbole. When developers like DHH and Linus Torvalds — people who have historically been sceptical of every trend — start acknowledging that AI is changing how they work, you should pay attention.

But recognising the magnitude of the shift doesn’t mean accepting every breathless prediction at face value. This is where the hype cycle model is genuinely useful. We’ve been through the peak of inflated expectations. We’re somewhere in the trough of disillusionment for the first generation of tools. But here’s the thing people miss about the hype cycle: the end of one cycle is often just the beginning of the next step up the abstraction ladder. Each generation of tools enables a new set of possibilities that triggers its own cycle of hype, disillusionment, and productive integration.

The question isn’t whether AI-assisted development is real. It is. The question is what the stable, productive equilibrium looks like — and we’re not there yet.

Will It Make Us Obsolete?

Not in the current generation. Here’s why.

Current AI models operate fundamentally within the boundaries of what they’ve been trained on. They can recombine, synthesise, and apply existing patterns in impressive ways. But they cannot generate genuinely novel architectural insights that aren’t latent in their training data. They cannot reason from first principles about failure modes they’ve never encountered. They cannot make the judgment calls that come from years of watching systems break in production.

The next generation of AI — whatever form it takes — is still years away, and its success is far from guaranteed. There’s no clear consensus in the research community about what the path to meaningfully more capable systems looks like. And the financial picture adds uncertainty: it’s not yet clear whether the financial markets will continue to tolerate the enormous capital expenditure and modest returns that characterise the current AI buildout. The investment thesis depends on future capabilities that haven’t been demonstrated yet.

There are also geopolitical considerations that the European engineering community in particular should be thinking about. Will US-built AI tools be weaponised for competitive advantage? Is it in our strategic interest to build critical development infrastructure on top of systems controlled by a small number of American companies? The rise of capable open-source models from organisations like Mistral and others suggests that the capability itself is becoming a commodity — which is actually good news for those of us who worry about concentration of power.

So no — not obsolete. But here’s the uncomfortable middle ground.

Even if AI doesn’t replace engineers, companies will adjust to the prospect of it. They’ll expect more output per engineer. They’ll restructure teams around AI-augmented workflows. The environment will become more volatile and less cosy. The engineers who refuse to engage with AI tooling won’t be fired by robots — they’ll be outperformed by colleagues who embraced the tools.

And honestly? There’s a decent chance that the current state of AI coding tools will be treated as “good enough” by many organisations. Not because it’s optimal, but because it clears a threshold of utility — the way VHS wasn’t the best format but was good enough to become the standard. The gap between “good enough for most use cases” and “genuinely excellent” may not matter to the majority of the market.

The Third Golden Age

I want to close with a framing that I think cuts through both the hype and the doom.

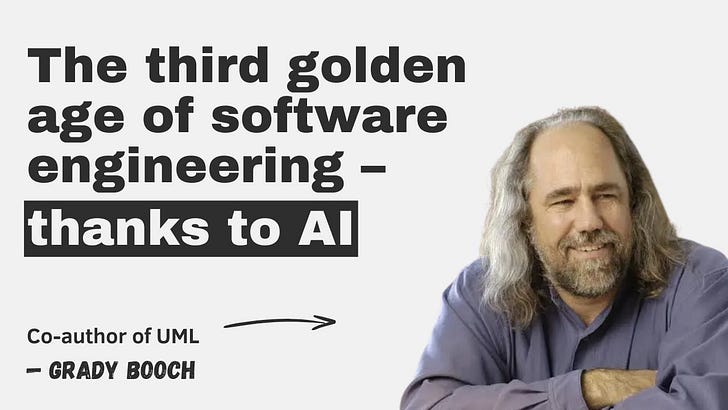

Grady Booch — one of the foundational thinkers in software engineering, co-creator of UML, and someone who has been thinking about this field longer than most of us have been alive — has described where we are as the third golden age of software engineering.

Image credit: The Pragmatic Engineer

Image credit: The Pragmatic Engineer

Gergely Orosz did an excellent deep-dive into Booch’s thinking in The Pragmatic Engineer — it’s well worth your time if you want the full picture. Booch’s framework goes like this:

- The first golden age (1940s–1970s) was about algorithms and computational theory. We figured out what computers could do.

- The second golden age (1970s–2000s) was about managing complexity — object-oriented programming, design patterns, software architecture. We figured out how to build large things.

- The third golden age (now) is about systems thinking — moving from individual components to entire platforms, with AI as an enabler of higher-level abstraction.

This framing is powerful because it recontextualises the current anxiety. Engineers have faced “existential crises” before. When compilers replaced hand-written assembly, people feared displacement. When higher-level languages emerged, the same fears surfaced. Each time, the profession didn’t shrink — it expanded and moved up the abstraction ladder. The engineers who embraced the new tools didn’t become obsolete. They became more capable.

That’s the pattern I see repeating. AI isn’t replacing software engineering. It’s moving us up an abstraction level — from writing code to directing systems that write code, from managing complexity to managing the AI that manages complexity.

What This Means for You

So, are we dinosaurs? I don’t think so. But we’re also not in a position to be complacent.

My commit graph tells one version of this story. An Engineering Manager who, armed with AI tools, became dramatically more productive as an individual contributor — while still doing the leadership work. The absurd CV project tells another version: that going deep with these tools requires genuine engineering skill, taste, and judgment. You don’t just prompt your way to a well-architected application. You bring decades of experience about what good software looks like, and the AI helps you get there faster.

The engineers who will thrive in this era are the ones who:

- Engage seriously with AI tooling — not dismissing it, not worshipping it, but developing real fluency

- Double down on the expertise that AI can’t replicate — production operations, security thinking, system design, understanding failure modes

- Embrace the role of operator — AI is a powerful tool, but powerful tools need skilled operators

- Move up the abstraction ladder — spend less time on boilerplate, more time on architecture, design, and the problems that actually matter

Booch says the opportunity is to redirect our attention “from friction to imagination.” I think that’s exactly right. The friction — the boilerplate, the repetitive patterns, the tedious plumbing — is increasingly handled by AI. What remains is the imagination: the ability to envision systems that don’t exist yet, to anticipate failure modes that haven’t happened yet, to make the judgment calls that no amount of training data can teach.

That’s not a diminished role. That’s a more interesting one.

Welcome to the third golden age.